From MBB News, "Magnolias and Chopsticks: The Mississippi Delta Chinese Experience Part 1," by Sandra Knispel, on 21 September 2011 -- The Chinese of the Mississippi Delta are an often-overlooked part of the history of the Deep South. In part one of our two-part series, MPB’s Sandra Knispel tells the story of what made them come all the way to the small towns of the Delta.

China is a long way from the United States. Yet many made the voyage, hoping for a better life. In the late 1860s, the first Chinese reached the Mississippi Delta. According to data collected by the University of Mississippi's Center for Population Studies, in 1870 only 16 Chinese lived in the Magnolia state.

“The Chinese were attracted to the Delta by plantation owners who were looking for cheap labor to replace many of the slaves who were no longer working on the plantations.”

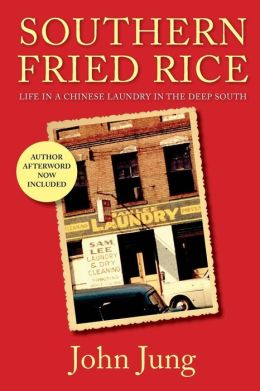

John Jung is a California State University professor emeritus of psychology and author of Chopsticks in the Land of Cotton and Southern Fried Rice, which both describe the Chinese experience in the Deep South. The plantation owner’s plans failed quickly when the new immigrants left sharecropping pretty much immediately.

Sot Dr. John Jung: That’s partly because the Chinese were able to find a more lucrative way of earning a living.” 6

That lucrative way came as small-scale grocers. Chinese immigration to the Deep South really began to pick up in the early 20th century. Luck Wing is a retired Delta pharmacist whose parents left China in the 1920s.

“For a better life, you know. The Chinese word for the United States back then was Gam Saan, that’s the Cantonese for “Gold Mountain.”

“The Chinese at home in China would literally think that all you needed to do was to come to the United States and work somewhat and you can share in the wealth,” says Frieda Quon.

Frieda Quon, a retired librarian at Delta State is like Wing is a second-generation Chinese-American. Both were born and raised in the Mississippi Delta.

“My father came at the age of 14 from a small village in China, Canton. And he came to Chicago to join his older brother who was already there in a laundry business."

Quon’s father came to the U.S. in the 1920s, originally on forged papers, pretending to be someone else’s child.

"So, when dad left, he was the youngest to come, he wouldn’t get to see his parents again. His father died, never saw his father again. He did get to see his mother but it would be years later.”

At some point in the late 1930s, her father moved 600 miles south, down from Illinois to the Magnolia state.

"My uncle heard about Mississippi and the better opportunities for [making] a living in Mississippi," Quon explains. So, he left my father, probably with a cousin or uncle or others, to run the laundry while he journeyed to Mississippi to investigate. So, yes, this was better than the laundry and so then eventually my father came to Mississippi as well.”

In the Delta, nearly all Chinese were small grocery owners, filling a void left by white plantation owners who had stopped the commissary business of selling goods to their black sharecroppers, often at rather unfavorable terms. Quon’s dad, too, had by now become a Delta grocer. But there was something else he wanted…

“In ‘39 or 1940, he went back to China to be married. And the custom then was to have a matchmaker. It was just willingly accepted. You know, my mom never saw dad before she married him. I think maybe they stayed for a brief time but then eventually both came on a ship and came to Mississippi.”

Unlike in the large urban centers of New York and Chicago where the immigrants lived in so-called Chinatowns, the Delta Chinese were largely on their own. Without a sizeable Chinese community around them, they ended up largely isolated in Mississippi’s rigid society.

“We were not with the white group and we were not with the black group. And so, I guess, we were somewhere in the middle.”

They quickly learned that in order to survive one had to tread carefully and keep mum. Public neutrality in the emerging civil rights struggle of the 1950 and 60s became second nature to most Delta Chinese. At some point, Frieda Quon’s family even owned two groceries in Greenville:

"The way the stores were arranged -- they were diagonally. One on Alexander and Eureka and actually the other one was on Alexander and Eureka. But one focused more on the trade for the black customers, and then the other one for the white customers. Two separate stores.”

The grocery stores proved to be the ticket to survival in the Deep South. And even today, scattered among the many shuttered business facades of the Delta, here and there are still some small surviving Chinese groceries… long past their heyday, often with old, sun-bleached neon signs, but nevertheless part of the Delta’s storied history. [source: MBB News--Sandra Knispel, MPB News.]

0 comments:

Post a Comment