As reviewed in the New York Times, "Masters and Slaves," by Andrea Stuart, on 29 March 2013 -- On a trip to Paris, I recently had the same shocked realization that Andrea Stuart describes in her astounding new book, “Sugar in the Blood.”

Slaves built this, I thought as I wandered from one grand 18th-century monument to the next. How rarely we acknowledge that Europe’s great cities were built on profits from the labor and blood of slaves cutting sugarcane half a world away.

Sugar in the Blood: A Family's Story of Slavery and Empire; by Andrea Stuart

Stuart, a London-based author of Barbadian ancestry, writes of contemporary England: “Sugar surrounds me here.” The majestic Harewood House in Leeds was built with money from Caribbean sugar plantations, she points out, as was the Codrington Library of All Souls College in Oxford and Bristol’s mansions. The slaves of the West Indies built this wealth while unaware of its existence, or of their own connection to it. Without them, the vast empire that gave the world Victoria and Dickens might never have existed.

In this multigenerational, minutely researched history, Stuart teases out these connections. She sets out to understand her family’s genealogy, hoping to explain the mysteries that often surround Caribbean family histories and to elucidate more important cultural and historic themes and events: the psychological aftereffects of slavery and the long relationship between sugar — “white gold” — and forced labor.

“Sugar in the Blood” begins in the late 1630s with Stuart’s maternal ancestor George Ashby, a young blacksmith in England, preparing for his voyage to the Americas. He was “most likely typical of the men who settled much of the New World, a man of action, not reflection, who did not take time out to write letters or keep journals,” Stuart writes, and she relies on historians and other personal accounts to flesh out his motivations, his reasons for migration and the “assault of newness” that was Barbados.

“As a Northern European, George Ashby was used to a palette permanently tinged with gray; here, the world was suffused with light and brightness. . . . The night was different here: the constellations disordered, the stars brighter and more prolific above him. The smell of the tropics was also novel: the intense perfume of flowers and spices mingled with the salty sea air and the warm fermenting smell of the earth.”

Much of the fiery magic of this book arises from Stuart’s ability to knit together her imaginative speculations with family research, secondary sources and the work of historians of the region, including C. L. R. James and Adam Hochschild. Stuart spins this rich material into a colorful and complicated narrative from Ashby’s arrival in Barbados in the 1630s up to 1835, a year after Britain abolished slavery, always attentive to the continuing repercussions of the plantation system in the United States and the Caribbean.

The book is full of wonderful characters. The early islands were awash with pirates, buccaneers, reprobates, criminals and the dissolute, depraved, discarded refuse of the motherland. Often these ruffians rose to high position in the New World — like Capt. Henry Hawley, known as the belligerent, “fire-eating” governor of Barbados, who had his predecessor executed and sold land to new arrivals. At a meeting with the daunting Hawley, ancestor Ashby acquired the original nine acres that eventually grew to a 350-acre sugar plantation where some 200 slaves labored.

Stuart also presents a full portrait of George’s descendant, the hard-nosed plantocrat Robert Cooper Ashby, who took over the plantation in 1795. We learn about his thorny relationship with his wife, Mary Burke, and with his many slave “concubines,” notably Sukey Ann, with whom he had four children and whom he finally freed just before abolition. We also learn much about the hard business of sugar cultivation.

One of the many pleasures of “Sugar in the Blood” is its author’s evocation of everyday life on the plantation. In one section, Stuart describes a day on the Ashby holdings (called Burkes, because most of Robert Cooper’s land came to him through his wife). This day is presented first from the detailed perspective of the planter and his family and then from the more broadly painted point of view of the slaves, who left little historical record of their presence, except when they were bought or sold.

It is easy, Stuart writes, to imagine the Ashby family “slumbering on canopied beds piled lushly with cushions and covered with embroidered sheets, as the ubiquitous bats soared and dipped against the starlit night and the plantation dogs barked their messages to their neighbors; or gorging on lavish plantation meals; or sitting on the balcony’s wicker furniture enjoying their lime water; or playing backgammon on the patio; or strolling in the garden against a backdrop of green pastures and a vivid sky, while the sounds of the slaves cutting cane wafted over to them from the far-off fields.” In the mornings, Robert Cooper Ashby would be awakened by his “body slave” (a dreadful term to add to the long lexicon of slavery), who would bathe, dry and dress his master and fix his hair. Ashby would descend to a breakfast that might include, as a visitor described it, “a dish of tea, another of coffee, a bumper of claret, another large one of hock negus; then Madeira, sangaree, hot and cold meat, stews and fries, hot and cold fish, pickled and plain, peppers, ginger sweetmeats, acid fruit, sweet jellies.” “It was a point of honor in plantation society that no menial activity was undertaken by anyone but a slave,” Stuart writes. “Cooper and his contemporaries would do as little for themselves as was humanly possible.” At night the body slave held the chamber pot for the master.

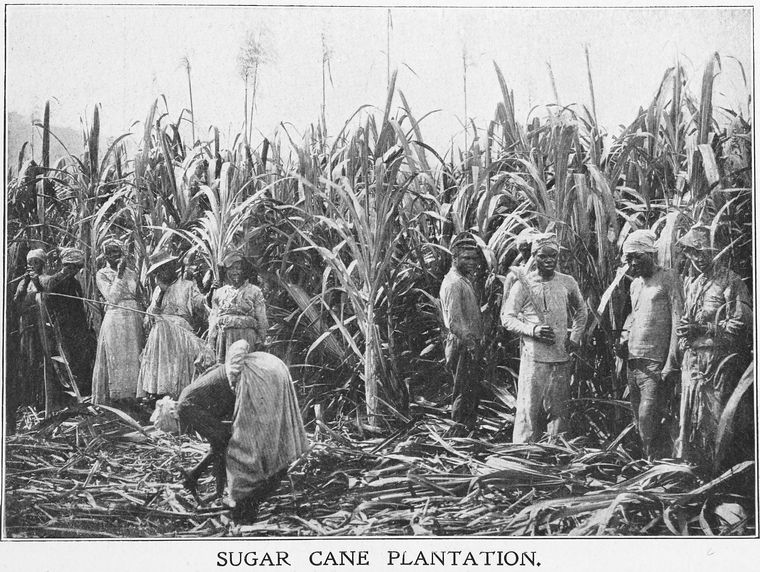

Meanwhile, the slaves were “woken before sunup by the clamoring sound of the bell atop the mill.” They “hauled themselves off the floors of their fetid huts and quickly splashed their faces with cold water before being led to the cane fields by the overseer.” They worked until 9 o’clock, when they were allowed half an hour to eat a bit of boiled yam or plantain. And back to work, with a midday break, until sundown or later. Upon returning to their quarters, they had “children to attend to, homes to be cleaned, allotments to be tended and food to be cooked.” During harvest, field hands frequently worked through the night. “More than one observer compared the scenes in the sugar mills to Dante’s inferno,” Stuart writes. “Near-naked slaves labored in the glow of the flames and the roaring noise and the ferocious heat of the boiler room.” Slaves worked up to 18 hours a day. Accidents were so common an ax was kept handy to slice off limbs caught in machinery.

But the book’s importance consists not only in such vivid and specific retellings but in how it explains the mentality of the masters alongside the predicament of the slaves.

Stuart feels complicit in both sides of the story she is telling. If Robert Cooper Ashby was her forebear, so was his concubine, the “unknown female (slave)” who gave birth to John Stephen Ashby, Stuart’s mother’s great-great-grandfather, of whom almost no record exists. She understands the white master and his cruelties, she understands the slave in her misery, and she understands the thwarted attempts of both to recapture their humanity. As Frederick Douglass said, “No man puts a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.” Stuart also illustrates how the exigencies of the sugar trade stand squarely in the middle of the suffering and moral confusion.

There is not a single boring page in this book, which — as a longtime reader of nonfiction and skipper of boring pages — I can attest is an achievement in itself. In every chapter of “Sugar in the Blood,” history, fact, analysis and personal reflection combine to move the narrative forward, both the grand story of slavery and sugar and the more mundane but always fascinating story of family and business. And beneath every banal moment of cooking or cleaning, of selling or buying, of dressing or undressing, the threat of uprising and rebellion beats loudly, as it must have done on the plantation.

Again and again, Stuart shows us the costs of what the historian Edward Brathwaite called “social processing,” in which white newcomers who were initially horrified by slavery began to accept its strictures and harshness. She quotes Lt. Thomas Howard, who served in the Caribbean in the 1790s: “When I first came into this Country . . . every time I heard the Lash sound over the Back of a Negro my very Blood boiled and I was ready to take the whip and the Lash of the Master. Since that time . . . I am persuaded my heart is not grown harder . . . yet I see the Business in a very different Light.”

Howard had come to understand that violence was critical to the plantation economy. Without it the inequalities and inequity demanded by large-scale sugar cultivation could never be maintained. Stuart disproves the “kind master” and “docile slave” stereotypes; every person she describes, whether slave, master or the wide cast of those “in between,” was trying to grab at whatever possibilities or luck might emerge from the inhumane system.

“Sugar in the Blood” brings us into the present day. The mill tower at Burkes plantation where the bell was rung calling the slaves to the cane is now the studio of a local artist who has built a “fashionable home beside it.” The master’s grounds at Plumgrove, a part of the Ashby family holdings where Stuart spent many childhood summers, is a housing development, and soon the great house will be turned into condos.

There may be liberty, equality and condominiums now, but slavery’s legacies continue. In many places in the Caribbean, skin color still counts, and the lighter — or brighter, as it is said — the better. Darker-skinned people, descendants of the slaves, still toil in unrewarding work, as chambermaids in tourist hotels along the beaches of Barbados, say, or in garment factories in Haiti — when they are lucky. And the lighter-skinned elite, descendants of master and slave, still function as a kind of aristocracy. Stuart is one of them, and with this powerful book she explains how she herself arrived in the complicated Caribbean, and she analyzes and, crucially, humanizes its conflicted, confounding legacy. [source: The New York Times; Amy Wilentz is the author, most recently, of “Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter From Haiti.”]

0 comments:

Post a Comment