From time to time it's good practice to view slavery as seen from the planter's perspective. For those who have never encountered it, this is an example of the "Happy Darkey" narrative that is so pervasive in the American myth. It's the food, clothing and shelter justification for 256 years of perpetual bondage and uncompensated labor. The author Robert Quartermann Mallard [R.Q. Mallard] 1830-1904 was a Presbyterian clergyman, who pastored of the Napoleon Avenue Presbyterian Church in New Orleans. (Ron Edwards, US Slave Blog)

The author, R.Q. Mallard, writes in a chapter entitled, "THE WRITER'S CONNECTION WITH SLAVERY AND SLAVES" :

PLANTATION LIFE BEFORE EMANCIPATION

CHAPTER V: The Negro - How He Was Housed, Fed, Clothed, Physicked and Worked

![Evolution of the Negro home; Slave - cabins, Southern United States [loaned by Southern Workman].](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_uKj4Ax2xYGslID0Ij4G2CyvJXrx_C3VdeMUaqWd3e5sXts8LIjaFG4SsFrz14-xl8aq1O1NoOkp5VTQaPTA2_Nzp9gwnLaXskiJ0zky3-cKPxi=s0-d)

The author, R.Q. Mallard, writes in a chapter entitled, "THE WRITER'S CONNECTION WITH SLAVERY AND SLAVES" :

IT was my lot from infancy to mid-life to have been intimately associated with that race whose premature enfranchisement wrought such temporary mischief in state, and whose present and future political and ecclesiastical status fills the hearts of statesmen and Christians alike with concern. I was the son of a well-to-do slaveholder, and myself, although never a planter, an owner at my marriage, by the generous gift of my father, of some of his trustiest and best servants, and also as trustee in my wife's right, and having our own servants always with us until emancipation.

The memories of that connection are of almost unmixed pleasure... I saw slavery under its most favorable aspects. My home was in Liberty county, Ga., where that curse of Ireland, landlord absenteeism, did not exist, the planters, almost without exception, visiting their plantations during the summer at least twice a week, and spending the six months, including the winter, among them ...

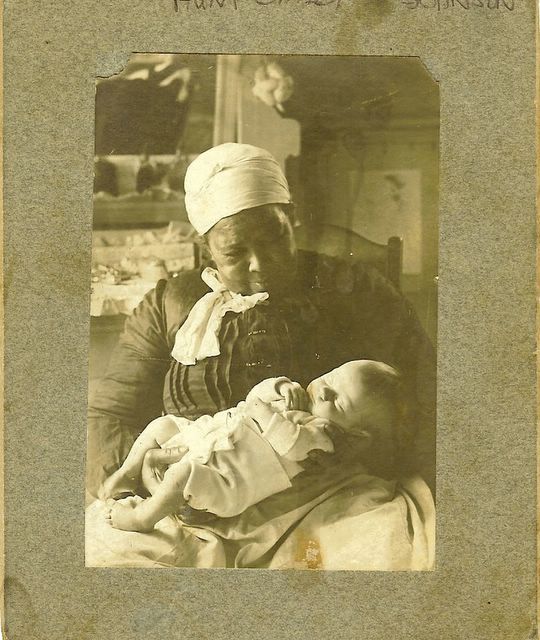

As a babe, I drew a part at least of my nourishment from the generous breasts of a colored foster mother, and she and her infant son always held a peculiar place in my regards. A black nurse taught me, it is probable, my first steps and first words, and was as proud of both performances as the happy mother herself. With little dusky playmates, much of my holiday on the old plantation in the winter season was passed. Some parents were in this matter more particular than mine. On one plantation, I remember, the rule was that the white and black children were both punished if found playing together. My association with them was, I admit, somewhat to the detriment of my grammar, a fault which my schoolmaster speedily remedied, but never to the damage of my morals... (source: Plantation Life, Before Emancipation; Chapter 2, 1891)

PLANTATION LIFE BEFORE EMANCIPATION

CHAPTER V: The Negro - How He Was Housed, Fed, Clothed, Physicked and Worked

IN this letter I shall speak, not without passing allusions to practices prevailing elsewhere, mainly of the general custom, with regard to the above matters, in my own native county; convinced that the representation will be recognized by the well-informed as a fair average picture of the conduct of the entire South.

The houses on some plantations were constructed of sawed lumber, furnished by the adjacent water- mills, or cut out by the negro sawyers laboriously, and not very accurately, with the whip-saw, worked in pen or pit, and making a tolerably fair joint possible. On our plantation they were, for the most part, covered with a weather-boarding of clapboards, split along the grain with what was called a frow, and from short cuts of cypress logs, and not admitting of a very close fitting. The houses were never lined within, so that only the thickness of a single board kept out the winter's air and cold. Usually the house had two or more unglazed windows, and a front and a back door, and was warmed by a clay chimney, with a wide hearth, abundantly supplied with oak and pine. You entered first the common living room. Separated from it, and with its door, was the family bedroom; and if the children were half-grown, you would find frequently one or two "shed-rooms," or leantos, in the rear, furnishing all proper privacy. The furnishing of the servants' home was primitive. There were a few benches and a rude rocker, all of home manufacture; shelves in the corner, containing neatly scrubbed pails and "piggins," made by the plantation coopers of alternate strips of redolent white cypress and fragrant red cedar, bright tins and white and colored plates, with the never absent long-necked gourd dipper, and beneath them the ovens, pots and skillets, the simple but most efficient paraphernalia of the mother cook.

The bedroom had a few boxes, containing the simple finery and Sunday clothes of the family; the week-day garments hung upon a string stretched across the corner; the bedstead consisted of a few boards nailed across a pair of trestles, and covered with the soft black moss so abundantly yielded by the adjacent swamps, and quite a number of good warm blankets, in which the sleepers, oblivious of change of seasons, would wrap themselves up, until not a square inch of sable skin was exposed.

Their food was mainly maize [corn], which, where a public mill was handy, was ground for them; on my father's place they ground it themselves on the common hand mill; also the sweet potato, abounding in starch, the main nutritious ingredient in all food products; and easily and quickly cooked in the ashes, or baked before a fire. The weekly allowance for a "hand" or full worker was, I believe, a peck of corn, and four quarts additional for every child; and a half bushel of sweet potatoes to each adult, and to each child in same proportion. This weekly fare the year round was with us supplemented, in the season when the work was unusually heavy, by rations of molasses, or bacon, or salt fish; and an occasional beef. To this, thrifty servants added rice, of which they were as fond as the Chinese, and which they cultivated themselves in patches allotted them, and with seed and time afforded by their masters; and chickens and bacon of their own raising and curing, and fish of their own catching. So abundant were the rations of corn, that at the end of a week the careful house-holder sent quite a bag of it to the store to be exchanged for calico or tobacco!

As to their clothing, two good strong suits were given every year - in the summer, white Osnaburgs; in the winter, a kind of jeans, partly cotton and mostly wool, and stout brogans. The clothes were often cut and made up "in the big house" by negro seamstresses. The house-women were clad in a very neat fabric called "linsey woolsey," and with the house-boys fell heirs to the half-worn garments of the young masters and mistresses. A good warm blanket was given each worker every alternate year; so that a little care accumulated an abundance of warm bed covering.

As for their physicing, this was largely, and not unskillfully, done by the planter himself. In each plantation library was a book of medicine - my father's, I remember, was "Ewell's Practice" - books written without technical phrases, clearly describing, in the language of the common people, diseases and their remedies.

As the maladies of the African, with his simple civilization, were rarely obscure, many planters acquired a very considerable skill in diagnosing and prescribing; and probably killed no more of their patients than the young M. D. graduate is said to kill, just in getting his hand in ! A big jug of castor oil was always on hand, but it had to be kept under lock and key, so fond was the darkey of dosing himself for any and every ailment with that antiquated and heroic remedy; another thing he had the utmost faith in was the lancet; for, according to his simple therapeutics, it let the bad blood out; just as rubbing a sprained ankle with cold water toward the toes would send the inflammation from their tips into nothingness!

When a case, however, was too serious or complicated, or obscure, for the planter's knowledge or skill, or obstinately refused to yield to the few remedies of his materia medica, Tom or Jerry was mounted on a swift horse and sent post haste for the doctor, five or ten miles away! Whenever we met a negro riding furiously, we always divined, "Going for the doctor," and were seldom wrong. He only checked up his foaming steed long enough to confirm our surmise, for it was his peculiar joy to tell the news, especially if bad. The doctor, it must be admitted, had but a poor chance either to cure or at his leisure to run up a bill, and this practice of only sending for his services in desperate cases depressed patient and doctor and nurses, and contributed sometimes to a fatal result. "To send for the doctor" was, in plantation belief, to give up the case; and the doctor's patients recovered only by a special miracle; but when they did not, they at least died secundem artem.

As for their work, they were never called out in the rain, and open sheds were always provided in distant fields against thunder showers. In some parts of the South they were, with an interval of a noon day rest of several hours, in the field from "sun up" to "sun down," but in all such instances their food was cooked for them, and they were generously fed upon full rations of bacon. With us the work was, in the main, extremely light. It was the duty of the men to split the pine rails with which the plantation was enclosed, to clear the forest from the "new ground" prepared for tillage. The women and the "thrash gang" - i. e., the half grown boys and girls - made up the fences, the men commonly drove the plow, the women never handled anything thing heavier than the hoe; in the harvest both used the sickle, the men threshed the rice and trod the cotton foot-gin, while to the women was assigned the easier task of sorting the lint of its specks and leaves. Our lands were light and friable and easily worked, and for a large part of spring and summer the hands were allotted task work; and many is the time I have in the spring season seen the industrious laborer shouldering his hoe, with the sun high in the sky, ready to work his own allotted patch in the rice field, or to go "churning" or lounging and gossiping in the village street!

Compare the average house of the slave with the one-roomed mud hovel of the Irish tiller in Roman Catholic Ireland, with no privacy by day or night; the suitable and substantial clothing and bed covering supplied the slave with the scanty and sometimes ragged raiment of the poor in our great cities, and even laborers in our factories; their big fires, wood ad libitum, with the miserable, smouldering embers over which the poor sewing women crouch shivering in Northern cities; the excellent nursing and good medical attention given the slave, with the condition of many of the poor work-people, who dare not, or will not in their pride, call in a physician, for whose services they are unable to pay; compare hours of labor in the open air, not pushed to exhaustion and comparatively short, with the long and drastic work of many artisans, against which there is a constant demand for restrictive legislation; and add to this the consideration, that if the white master lived in comparative luxury upon the fruit of the labor of his slaves, he had all the care and forethought and responsibility of directing and organizing the labor for united efficiency; in a word, that he supplemented the African brawn with Anglo-Saxon brain; and it will be perceived that no laboring population in the world were ever better off than the Southern slaves; and that there never was a falser accusation made against the Southern planter than this, harped upon by abolitionists of old, and repeated sometimes by Northern preachers now, that "he kept back the hire of the laborer."

The plain truth is just this, that no tillers of the soil, in ancient or modern times, received such ample compensation for their labors. He was not paid down, it is true, in cash, but he was amply compensated for his toil in free quarters, free medical attention, free food, free firewood, free support of sick, infirm, aged and young, and the free supply of that organizing faculty which utilized labor and made it more productive and capable of supporting, without the remotest fear of starvation, or even of scarcity, and without appeal to public charity, of entire slave communities, often as large as that of a good-sized village of whites!

(source: Documenting the American South. Mallard, R.Q., PLANTATION LIFE BEFORE EMANCIPATION, "Chapter 5," Richmond, Virginia. Whittet and Shepperson 1001 Main Street, 1892. Pages 29-36.)

0 comments:

Post a Comment